In addition to creating our earth-friendly natural landscapes full of native plants, one of the most important things we can do is to participate in community science projects, formerly known as “citizen science.” Wild Ones now uses the term “community science” since it’s more inclusive and accurate.

The Xerces Society has a good definition of what this is:

Community science (sometimes referred to as “participatory science” or “citizen science”) is a form of research that provides everyone—regardless of their background—an opportunity to contribute meaningful data to further our scientific understanding of key issues. By engaging community members, researchers can collect a larger amount of data, and often span more geographic regions, in a shorter amount of time. In turn, data collected informs larger conservation efforts. It’s also a great opportunity for participants to learn more about species that interest them. It’s a win-win situation for all of us—including invertebrates!

These projects have proliferated over the last few years, harnessing the power of laypeople to be the eyes and ears of scientists. All of us can make significant contributions to conservation. To collect the amount of information needed, it’s essential that we all make these observations!

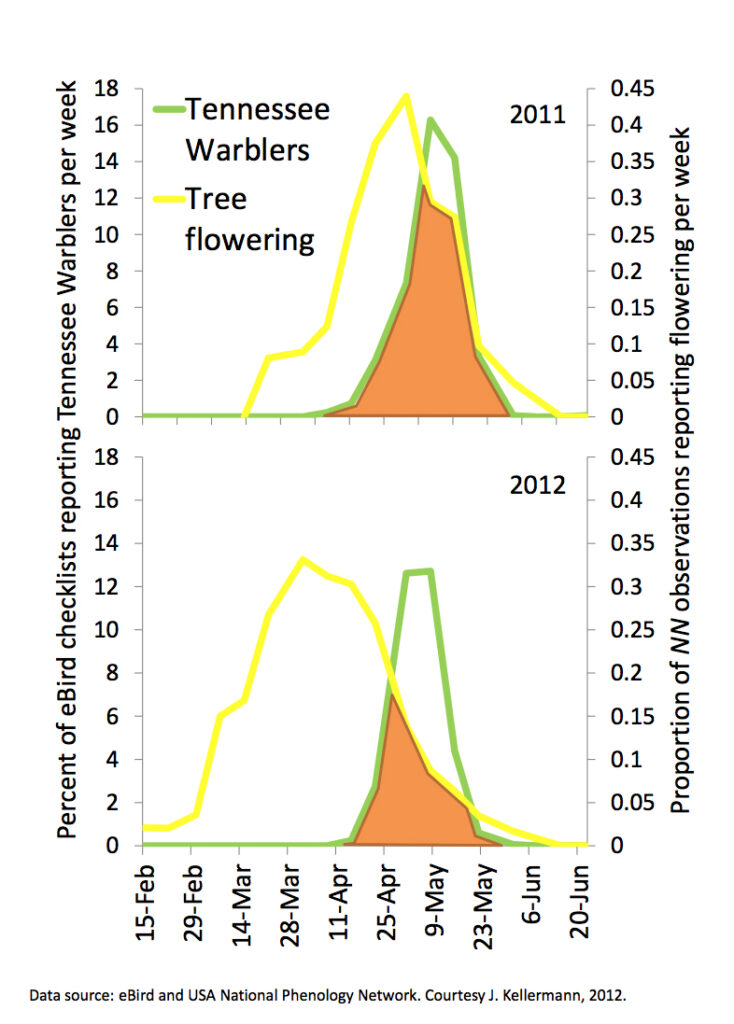

For example, the changes in the timing of warblers and tree flowering shown in this graph from the USA Phenology Network wouldn’t have been detected without the contributions of many community scientists like ourselves.

Some of these projects take us out and about, many can be done right in our own yards, and some from the comfort of our family room or even just in front of our computer.

In addition to being a way for non-scientists to make important contributions to conservation efforts, these projects sharpen our observational skills, prompting us to notice habitat happenings that we might never have noticed otherwise.

For example, besides appreciating the beauty of native honeysuckles, we also became alert to the timing of the blossoms.

NOW is the time!

Each year that goes by without collecting observations loses valuable data that is never recovered. We’re fortunate to have data from long ago to compare with today’s sightings.

For example, “The detailed record of bird sightings and phenological observations around Concord, Massachusetts—from Thoreau’s notes 170 years ago to today’s studies by scientists at Boston University—provides a key to studying how climate change is affecting bird migration.” ~ Living Bird magazine, “At famed Walden Pond, spring is coming earlier than it did in Thoreau’s day”

Fortunately, people have been participating in community science for a number of years, and conservation efforts are already benefiting. Here’s an example of the treasure trove of data about hummingbird migration collected by Journey North for 25 years.

Projects we enjoy

There are a LOT of community science projects! Many hundreds are described at SciStarter.org, and they include not just nature-oriented projects, but projects related to astronomy, human health, and many more topics. You can filter for the ones most suitable for your interests and abilities.

Back in the “olden days” pre-internet or smart phones, we had to record our observations on paper and send the results in by snail mail. Later, we could record them and then enter them on the project websites. Now, with the introduction of mobile apps, these projects have become MUCH easier — making the observing and submitting the information a one-step process!

Below is a list of some community science project categories we HGCNYers might most want to participate in. Go to each page for a description of the projects.

Resources

Latitude/Longitude:

Some projects require or at least prefer having your latitude/longitude for greatest accuracy. Generally two decimal places is sufficient.

One way to get this is through GoogleMaps. Find your location and click on it; your latitude and longitude will be displayed.

Another way is to use LatLong.net, which is what Monarch Watch recommends for their Monarch Calendar project. For just finding your lat/long coordinates, you don’t need an account or to log in.

Reflections

Citizen science-powered algorithms are now going beyond individual organisms. They’re mapping their relationships to an entire ecosystem, from the flower a butterfly pollinates to the leaf where the insect lays its eggs. … Ultimately, the apps’ greatest breakthrough may not be technological at all. It may be raising our awareness. We are nearly blind to entire categories of living creatures. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer described it as “being lost in a foreign city where you can’t read the street signs,” a form of species loneliness. While these plants and animals are our neighbors, we scarcely acknowledge their existence, let alone their right to exist. … By naming my wild neighbors, I’ve found my perception of them transformed from grainy and distant to powerful and familiar.

~ Michael Coren, Washington Post Climate Advice columnist